What is the first thing that comes to your mind if I say “gender”? And what do you think about if I say “gender equality”?

I am ready to bet that most of you will have instantaneously thought about “female and male” as a reply to the former question, and about “women” – or more specifically “women empowerment” – in relation to the latter. While there is nothing intrinsically wrong in these answers, at the same time it stands to mention that they are partial and they deeply suffer from a lack of problematization, thus representing only one of the many facets that compose the complex concepts of “gender” and “gender equality”.

“But if we had had more time we would have answered in a more comprehensive way”, one might argue.

True. But the real issue is not when we fail to grasp the real complexity of such concepts, rather when this lack of problematization happens at a policy-making level, especially when the aim of such policies is to enhance, stimulate and – finally – deliver development. It did not take much for policy makers and academics to recognize the fundamental role gender plays in development, but concretely incorporating it into effective policies was a whole other story.

Initially, the focal point for development studies was indeed the role of women and how to better their lives around the world. Why (only) women? Because in 1970 Ester Boserup published her book Woman’s role in Economic Development, which brought to light the extent to which third world economies are propelled by women and stated that programs considering women’s roles would lead to greater contribution to development. It served as a springboard for the flourishment of future studies and the development of the two theoretical approaches known as “Women in Development” (WID) and “Women and Development” (WAD). As much as it would be interesting to inspect the differences between them, it goes beyond the scope of this article. Instead, what matters is that WID and WAD further evolved into what today falls under the label of “Gender and Development (GAD) studies”. By focusing on “gender” in a broader sense over “women”, the GAD approach aims at paying due attention to the ways gender relations are socially constructed, beyond the typical binary construct.

“What’s the missing ingredient to make gender out of women?”, one might ask.

“Men”, one might think.

As a matter of fact, GAD did include the male variable into the equation. Needless to say, this was easier said than done. Notably, GAD initially started exploring the ways in which attitudes and practices of men affected women’s prosperity and positions. At first, the role of men was focused on –for example– how it affects the spread of HIV/AIDs, violence against women, and in opposing women’s empowerment. It took some time before approaches in GAD evolved out of this misconception of simply seeing men as the problem and started incorporating men into developmental policies in a “constructive way”. Even so, helping men was merely seen as an adjunct to channeling resources to women and supporting feminists organizing, with the view of enhancing women’s positions in society so that gender inequality would not remain ghettoized as a women’s issue.

As much as we could all agree on the fact that gender equality is an “everybody’s issue”, failing to address men’s issues in and of themselves as opposed to bringing men in, only in relation to their role in advancing women’s status, misses the point and risks provoking dangerous backlashes. Women-centered projects have indeed faced some sort of hostility from men, as they found themselves left out of the development agenda, and challenged in their own personal and socially inherited view of how a man should be and what he should do as a result of the changes accompanying those same projects. Take, for example, microcredit programs targeted to women in the Global South. Whilst seeking to add leadership development and personal skills to economic empowerment in women’s lives, such initiatives often provoked an increase in household violence as a consequence of men feeling emasculated and unable to fulfil their socially prescribed role of “breadwinners”. As my Professor once put it: “gender is relational” and, thus, we need to carefully account for both perspectives, without neglecting the dense network of familial, economic, cultural and marital roles in which gender relations are naturally embedded.

“Not as easy as we thought, but at least now we know and we can finally design gender sensitive policies that succeed in delivering development, right?”

“More or less”.

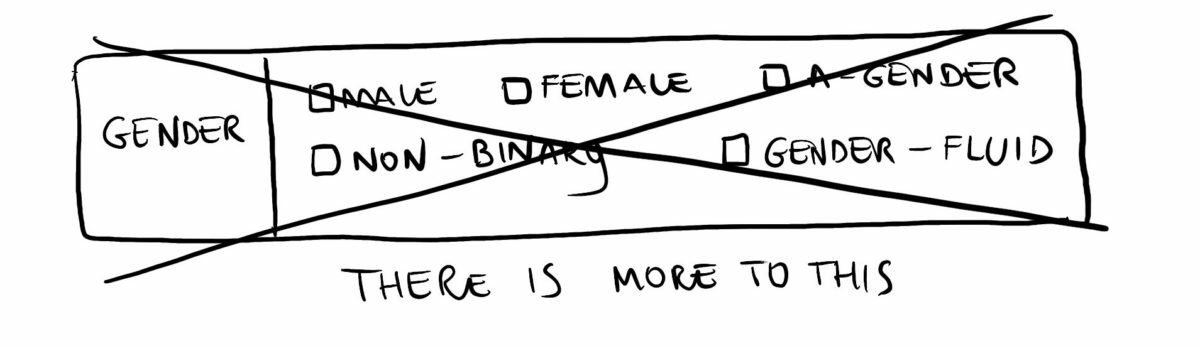

Incorporating masculinity and gender roles into development studies has undoubtedly improved researches in the field. However, beyond the complexity added by the introduction of the “male variable”, we are nowadays witnessing the recognition of new gendered identities. Defining gender in binary terms has become anachronistic, besides not quite appropriate. Since 2011, LGBTIQ+ people have been given a rights-based space –at least at a rhetorical level– in GAD studies, making the equation considerably harder to balance. The complexity that arises when the subject of analysis expands to include multiple dimensions of social life and categories of analysis is intrinsic to the subject itself, i.e.: human nature. As gender and gender relations are in a continuum, they are ever-dynamic and, therefore, we can reasonably expect such evolutions, entrenchments and intertwining to continue for as long we as human beings exist. Going beyond binary constructs seems now more needed than ever in order to retune developmental policies to tackle the intersectional issues at play in the life of individuals worldwide, while – finally and hopefully – delivering development.

I am conscious to be leaving you with more questions than answers, but this is precisely my point. If we had all the answers, that would mean that we could account for all the variables that make up reality as we know it. Maybe a good starting point would be to simply acknowledge that this is not the case and to start approaching development in a more context and culture-sensitive way, without trying to impose fictitious categories onto a reality that is clearly too complex to be put into boxes.